Affiliate Disclosure: As an Amazon Associate, Automoblog earns from qualifying purchases, including the movies featured here. These commissions come to us at no additional cost to you.

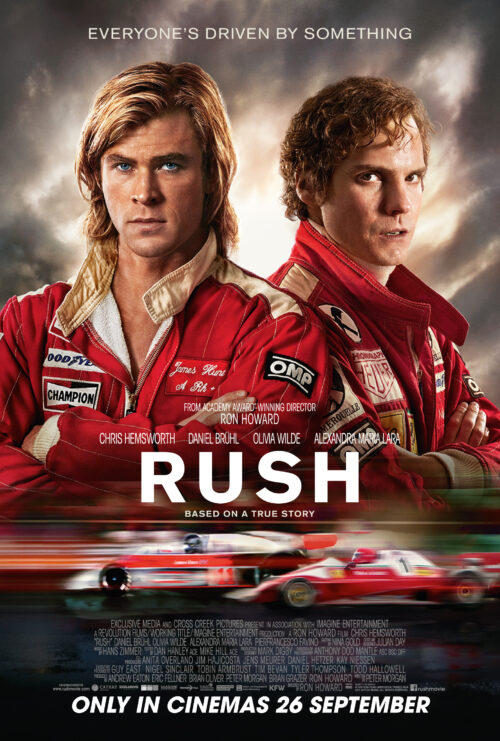

There are well-made car movies and Ron Howard’s 2013 film Rush is most definitely one of them. It tells the story of the rivalry and odd friendship between James Hunt and Niki Lauda throughout the 1976 Grand Prix season. It tells the tale captivatingly and cleanly about two of the most interesting characters ever to strap on a helmet.

Rush starts with Hunt and Lauda as up-and-coming racers in the lesser formula. These early sequences set the tone, both for the time period and for the two main characters. This was the 70s, and Grand Prix racing was a little more rough and tumble than it is these days. That’s easy to get across. What is not as easy to convey, and which Howard does masterfully, is the subtly of the personalities involved and their complexity as human beings.

The Universal Law

As the movie progresses, Hunt and Lauda quickly find themselves at the very top of the heap: Formula 1, Hunt with McLaren, and Lauda with Ferrari. Back and forth, the title fight swings as two of the heaviest heavyweights of all-time trade the championship lead race after race. And then a real-life racing curve ball hits. Lauda has a terrible accident in Germany. The ball of fire and ensuing medical recovery is adeptly shown by Howard in just enough gruesome detail to drive home a Universal Law: You can die in racing.

Until Lauda’s crash, there was talk of statistics (usually from Niki himself). There was talk of the number of accidents, injuries, and chances of death a professional race driver faced at that time. But with Lauda’s big accident, Howard contrasts it with bright orange light from the flickering flames of Lauda’s car, “Those are just numbers. This is the reality.”

And that’s the end, right? Lauda dies, and Hunt wins the championship? Oh no, no, it’s not. That accident at the Nürburgring happened with a third of the season left. After being read The Last Rights (twice!) and being implored by his doctors never to race again, Lauda is back in the cockpit at the Italian Grand Prix six weeks later.

Rush Is The Real Story

And this is where Ron Howard shows us what a real filmmaker is made of. It’s not about legends or machinery or special effects. It’s about the people involved and what they go through, their inner labors and outer manifestations utterly stripped of pretense. There is nothing added. There are no fabrications, and there is no sugar coating. These are the facts. This is what happened. It’s no surprise Rush was made by the same guy that made Apollo 13. They both show the same brushstrokes and unshakeable commitment to an immutable truth: a great story needs nothing but good telling; no embellishments, no decorations.

The casting for Rush was right on the money but still interesting in a couple strange ways. For a start, Chris Hemsworth plays James Hunt. In real life, Hunt was this odd, rubbery, and loose-jointed British kid. Tall, at 6’1″, it always looked like a stiff breeze could blow him over. The fact Chris Hemsworth, the guy who played Thor, could pull this off is rather remarkable. I mean, Thor’s huge, and he’s a literal comic book hero. He’s got arms the size of my legs. But Hemsworth does it and has James Hunt down to a “T.”

In a similar way, so does Daniel Brühl playing Niki Lauda. He looks like Niki (both before and after the crash), but that’s not the amazing thing. The amazing thing is how he has Lauda down pat. Say what you want about Hemsworth playing Hunt, but at least James Hunt had a personality.

Niki Lauda? I dunno, man . . . I met the guy before, and he was just like Brühl played him in Rush. Lauda is a collection of ticks, mannerisms, odd gestures, and pauses for computational collations of facts that are delivered upon you with all the directness and subtlety of a point-blank howitzer round. The guy had zero tact and zero thought towards the feelings of others. The only thing that made Lauda sufferable was that he was, annoyingly, right most of the time. And Daniel Brühl hits it out of the park in this aspect.

Other good jobs in the acting department come from Olivia Wilde as Hunt’s supermodel wife (and how Hunt ever got married in the first place deserves a movie of its own). Christian McKay does a spot-on version of the champagne swilling, let the good times roll Lord Hesketh (Hunt’s team owner), and Stephen Mangan pulls off a hysterically foul-mouthed McLaren head guy Alastair Caldwell.

Editing & Cinematography

A film editor once said to me, “Editing can make or break a film, but nothing, and I mean nothing, can compensate for a bad script.” And he’s right. Luckily Rush has a pretty good script. It leaves a few things out (Niki’s time at March, for example), but more importantly, it adds nothing. Howard is confident in his ability as a filmmaker to handle a story. He knows, by this point in his career, the best thing he can do is get out of the way and let the story, as it happened, unfold for the viewer.

If you think someone like Ron Howard is going to goof up the mechanics of making a film, you are looking at the wrong fellow. While I might have some personal issues with films he has made in the past, I could never say they are incompetent. The same goes for Rush. There’s not a dropped frame, obvious continuity error, camera shake, or bad cut to be found. The CGI, which is there if you know where to look, is cleverly combined into the background action, never the foreground work.

All the cars are real. All the driving is real. The digital stuff is just used to make you think you’re seeing a wide shot of the Nürburgring or a biblical downpour at Fuji.

There are a few shots that leave you shaking your head in a good way – and the cool thing is they’re not overly flashy shots. There’s a camera mounted on a wheel gun as it goes in to change a tire and another shot that looks like the camera is inside a driver’s helmet, staring into his eyes. And yeah, the sound design is exactly right. From the click-clack of a Hewland gearbox to the menacing build of a flat-12 Ferrari heading for its stratospheric redline. Technically speaking, Rush is a 10 out of 10.

Who Will Enjoy Rush?

Sure, you and I will say, “A movie about the Hunt/Lauda years? COOL!” The real problem is selling it to a non-gearhead audience. Does Rush work in that respect? Sort of.

A lot of reviewers liked it and praised not just its technical proficiency but also its broader appeal. The box office tells a slightly different story, with the returns making it only a fair to middling success. It made money, tripled it, actually, but it wasn’t a billion-dollar earning blockbuster, and in modern Hollywood, that’s the only thing that counts as a “success” these days.

What’s in Rush for us busted-knuckle, grease-stained, track day gearheads? Fricking everything! If you’re one of those few that loves cars but doesn’t like racing, it might not work 100 percent of the time, but for the rest of us, this movie presses all our buttons. Howard handles the subject with a great deal of affection and honor. He never talks down to us, and Rush never condescends. The “as you know, Bob” moments are few and very far between, and he has a great talent for showing and not telling.

And for us gearheads, there are visual and aural treats aplenty. You get up close and personal with some very lovely and exotic machinery like Ferrari 312s and McLaren M23s. Shoot, just the backgrounds of the racing shops are worth hitting pause and geeking out for a long while.

Should you, the gearhead, own a copy of Rush? You mean you don’t already? It’s available for rent or purchase on Amazon Prime. If you are looking for some other awesome car movies on Amazon Prime, take a look at our top picks and suggestions.

Longtime Automoblog writer Tony Borroz has worked on popular driving games as a content expert, in addition to working for aerospace companies, software giants, and as a movie stuntman. He lives in the northeast corner of the northwestern-most part of the Pacific Northwest.